While interest in African photography has swelled over the past 20 years, extreme temperatures and improper storage have threatened the physical integrity of important African photo collections, and due to their high commercial value, these photos are vulnerable to theft and mistreatment, putting them at risk of being lost forever.

One College of Arts & Letters researcher is working with an international team to address these issues in Mali by creating a digital archive that preserves the nation’s cultural heritage, safeguarding the photos from theft and further damage, while providing access for education and scholarship, raising awareness to this issue, correcting misconceptions, and inspiring others along the way.

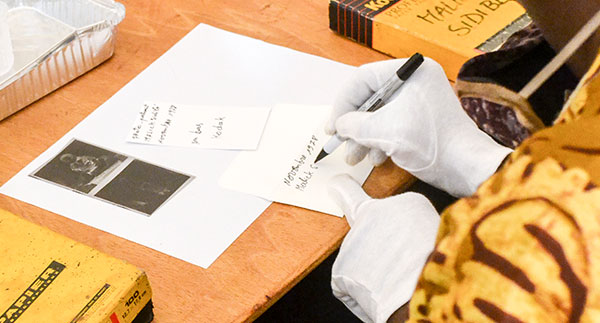

Since 2011, MSU’s Candace M. Keller, Associate Professor of African Art and Visual Culture in the Department of Art, Art History, and Design, has led a team of photographers, archival proprietors, conservators, and students that has restored, digitized, cataloged, and rehoused more than 100,000 black-and-white negatives dating from the 1950s to 80s. The materials hail from the archives of five prominent Malian photographers: Mamadou Cissé, Adama Kouyaté, Abdourahmane Sakaly, Malick Sidibé, and Tijani Sitou.

The Archive of Malian Photography project includes a free, publicly accessible database featuring low-resolution versions of the photos, making them accessible for research and scholarship. The work was funded by a two-year, $52,000 grant from the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme and a subsequent three-year, $300,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Preservation and Access Division.

“There has been a lot of excitement about the project in Mali, a lot of appreciation and pride in their history,” Keller said. “There is a feeling that more people should know about these histories and more people should have access to these materials so they become part of our global cultural history.”

Correcting Misconceptions

Prior to this project, the only substantial online archives of this kind that existed were of photos taken by Westerners who had traveled to Africa, but none of photos taken by Africans for African audiences. Seven years later, this is beginning to change.

“These images can tell a different narrative. They can present a different story from African perspectives about African realities, which we really need in order to be better world citizens,” Keller said. “Picturing modern cosmopolitan societies at various moments during the 20th century, these photographs challenge Western misconceptions about Africa.”

These images can tell a different narrative. They can present a different story from African perspectives about African realities, which we really need in order to be better world citizens

-DR. CANDACE KELLER

Now through October 2018, several photos from the Archive of Malian Photography are on display at the MSU Museum as part of the Five Photographers of Mali exhibit.

The Archive of Malian Photography images offer a unique perspective on local histories and practices, including photos of military activities, foreign dignitary visits, prominent religious leaders, political figures, musicians, cultural ceremonies and icons, personal and family portraiture, and the construction of national monuments, governmental structures, bridges, dams, and roadways. They also illustrate fluctuating trends in personal adornment, fashion, popular culture, and photographic practices.

“They are really stunning, powerful images, and there’s a lot that can be learned from them,” Keller said. “There’s so much history that is being preserved.”

Preserving Heritage

The Archive of Malian Photography project stems from the research Keller has conducted since 2002 on the histories of photographic practice in Mali. That research has enabled her to work with more than 150 photographers and their families throughout the country. Through these interactions and partnerships, she has learned about their primary concerns, which include the physical preservation of the archives.

“Their photographs are not stored in archival-safe materials,” Keller said. “In the best cases, they are kept in mailing envelopes that are not acid-free, housed in cardboard boxes or metal trunks in the back room of a studio or in an attic where there is a lot of dust. In the hot season, midday temperatures often reach more than 120 degrees, and these environments typically lack air conditioning. In such cases, negatives can adhere to one another and many of them have been damaged by heat, flooding, and abrasion.”

The other main concern is the archives’ vulnerability to theft due to their global commercial value. Since the late 1990s, an international market has grown for photos taken by West African photographers during the 1940s through 1980s.

They are really stunning, powerful images, and there’s a lot that can be learned from them. There’s so much history that is being preserved.

-DR. CANDACE KELLER

“Over the years, some unscrupulous dealers, collectors, curators, and even scholars have offered to ‘borrow’ negatives from certain archives in order to exhibit reprints overseas,” Keller said. “They promise to invite the family to the opening and to return the negatives at that time. Unfortunately, the family is rarely informed of such events. Rather, the negatives are taken to another country, often in Europe, where exhibitions are held and prints are sold. The photos have been printed in calendars, made into postcards, published in catalogs and articles, and sold online without permission. The families want the negatives back, but they typically never see them again.”

To protect the archives from further exploitation in global markets while increasing their public accessibility around the world, the project only provides access to low-resolution photos on the Archive of Malian Photography website and at the Maison Africaine de la Photographie in Mali’s capital city, Bamako. As a result, the images are commercially unusable in print. Yet, they are freely accessible to research and scholarship and able to be studied in detail on screen.

“One of the things I like about working in the digital humanities, and why we began this project, is that digital media can enable greater access, to a greater number of people, in more languages, and with more transparency than traditional print publications,” Keller said. “In this case, it seemed to be the best way to address specific concerns that were raised by photographers and their families, who are often the custodians of these archives. Over the years, many of these individuals voiced the same needs and so we worked together to address them.”

Creating a New Model

When work on the Archive of Malian Photography first began, a few similar projects existed, but on a much smaller scale and not near the magnitude or international scope. Now there is more interest in doing this kind of work in other countries, and the project’s team sees its role as one of outreach, to have their project set an example from which others can learn.

“One of the things our website does is post all of our workflows, contractual agreements, and tutorial videos so anybody can see the way we negotiated and collaboratively managed the project, and what we learned were best practices,” Keller said. “Rather than reinvent the wheel, they can emulate, revise, and improve upon them, if they wish.”

With additional funding, Keller hopes the collections of more photographers can be added to the Archive of Malian Photography database.

“We’re continually looking for more funding in order to incorporate more photographic archives within this project,” she said. “We have processed more than 100,000 negatives now, which is a small fraction when you think of all that exists, including national press archives and those of photographers who worked in other cities and regions at various historical moments. So, it’s a work in progress. I imagine this will be a project that I will be engaged with for quite some time and, I expect, it will affect my research for years to come.”

Currently, the team is working on the photo archives of Félix Diallo, which will soon be added to the archive website, making it the sixth collection to be included in the online database.

The Archive of Malian Photography is a partnership among faculty and staff in MSU’s Department of Art, Art History, and Design and MATRIX: The Center for Digital Humanities and Social Sciences at MSU; representatives from each photo archive; photographers working with each collection; photography students from the Center for Photographic Training; translators from the École Normale Supérieure in Bamako, Mali; undergraduate and graduate research assistants at MSU; the Maison Africaine de la Photographie in Bamako; the Malian Ministry of Culture; and the U.S. Embassy in Bamako.

Why Study African Art?

Keller’s decision to study African art goes back to when she was a child growing up in a multicultural San Diego neighborhood. She was intrigued by all the different worldviews and experiences found within her community and was curious about other cultures and diverse ways of being.

In college, she followed her interests, which ultimately led her to art history, explaining: “It involves philosophy, political science, history, religion, anthropology, etc. For me, art and visual culture are the most engaging lenses through which to explore, think, and talk about all these things.

As an undergraduate at San Diego State University, Keller studied every aspect of art history – ancient through contemporary Chinese, Japanese, Native American, Mesoamerican, U.S., South Pacific, European, African – and said she loved it all, but especially African art, which she chose to focus on in graduate school. She earned her M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in African Art and African Studies at Indiana University, Bloomington, and the love her graduate advisor, Patrick R. McNaughton, showed for Malian art and culture made an impact.

“I loved the language and so many cultural aspects in Mali,” Keller said, “and the art is incredible, so I really wanted to study it.”

While writing a graduate paper on two internationally renowned photographers from Mali, Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, Keller couldn’t find much information available so she chose this area for her research and received Foreign Language and Area Studies and pre-dissertation scholarships to travel to Mali to meet Sidibé (Keïta passed away the previous year).

“He was happy to see a young person interested in studying the language and culture and wanting to spend time learning about the history,” Keller said. “He wrote a letter for my Fulbright-Hays application and I’ve been working with him and his colleagues ever since.”

Learn more about Candace M. Keller and her research at her website.

Listen to Candace Keller and MATRIX Director, Dean Rehberger discuss the Archive of Malian Photography project on the Liberal Arts Endeavor podcast below.