Long before he became a Professor of Theatre Studies and Integrative Humanities at Michigan State University, Philip Effiong Jr. was a child struggling to survive a war the world would largely forget. During the Nigeria-Biafra War, he endured air raids, hunger, and displacement — experiences that left lasting psychological and emotional scars. Decades later, those memories have become the foundation of two memoirs through which Effiong revisits the conflict and examines its enduring impact on individuals, families, and communities.

Effiong’s perspective is shaped not only by his experiences as a child, but also by his family history. His father, General Philip Effiong, was a senior Nigerian military officer whose career is closely linked to some of the most defining moments in Nigeria’s history. During the Nigeria-Biafra War, he served as Chief of General Staff and Vice President of the secessionist Republic of Biafra. In the conflict’s final days, he assumed leadership of Biafra as Head of State and was the one who announced Biafra’s formal surrender, bringing the war to an end in January 1970.

“In recalling the war, I am acutely conscious of my father’s position as second-in-command in Biafra, a role that has cast him simultaneously as hero and villain,” Effiong said. “This awareness complicates my narrative, as I struggle to determine whether to present myself as an innocent child, a detached observer, a pitiable victim, or a complicit participant in the strand of history that has vilified my family.”

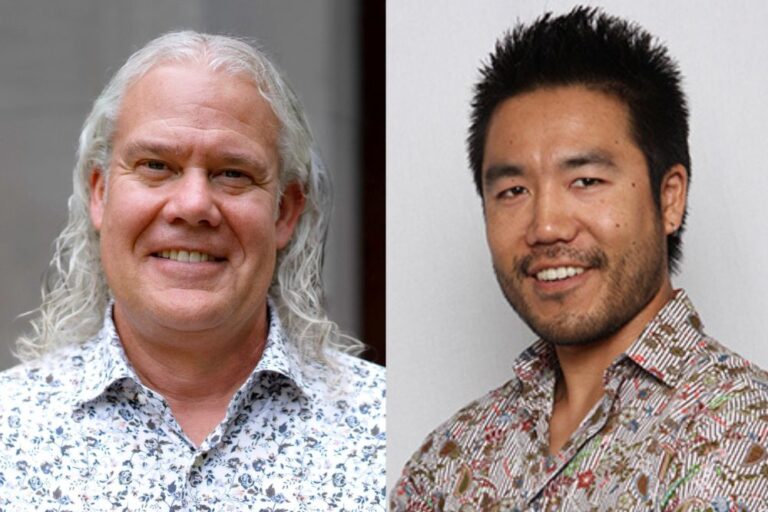

Now in his ninth year as a member of MSU’s Department of Theatre faculty, Effiong carries those complexities into the classroom. His lived experience informs a teaching philosophy grounded in global awareness, historical context, and the power of storytelling to foster understanding.

For him, telling his story is not about reopening the past but rather refusing to let it disappear.

“As I got older and became an educator, I realized that this is history. It’s sad history, tragic history, but it’s important history. We need to learn from it to understand how such violence might be prevented in the future.”

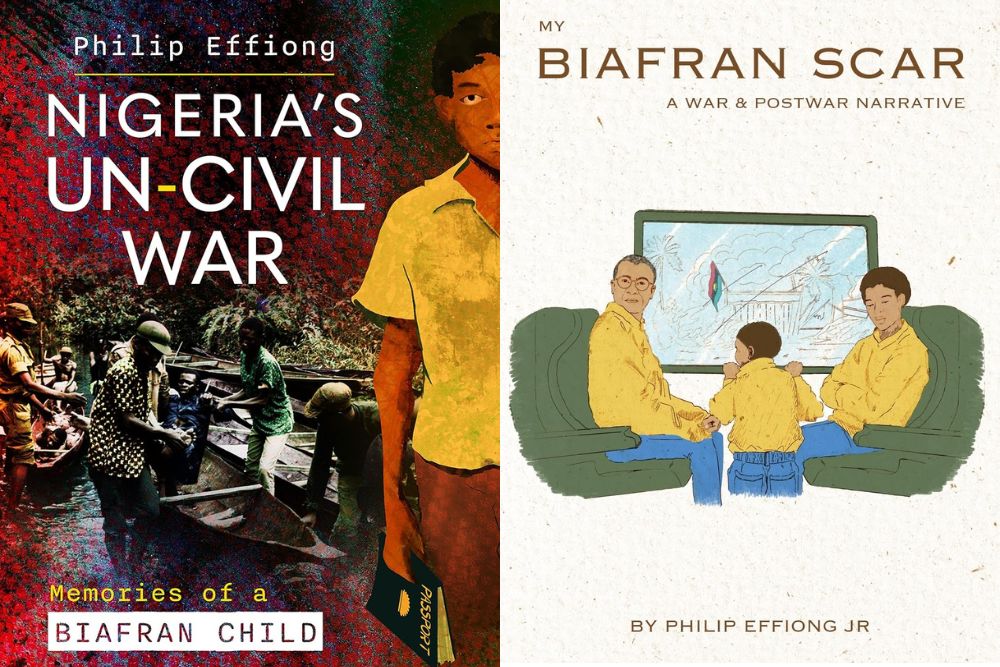

His first memoir, Nigeria’s Un-Civil War: Memories of a Biafran Child, recounts the conflict through the eyes of a child, focusing on the daily struggle to survive amid the chaos of war. His second book, My Biafran Scar: A War & Post-War Narrative, expands the story into the aftermath, examining the economic, psychological, and social consequences that persisted long after the fighting ended.

“It was very traumatic. I didn’t realize that it had such a tremendous impact on me psychologically and mentally,” Effiong said. “Even though it happened many years ago, I can remember vividly things that happened then but sometimes can’t remember things that happened just a few years ago.”

That realization became the starting point for his writing — an effort to recover stories long suppressed about a conflict that remains largely absent from global historical discourse. For Effiong, his memoirs are not only personal reflection but also an ethical act of remembrance. They reflect his commitment to preserving history, confronting trauma, and helping readers better understand the enduring cost of war.

“For a long time after the conflict in Nigeria, there were deliberate efforts to suppress the story. It wasn’t really carried in the media. Academic institutions hardly focused on it,” he said. “As I got older and became an educator, I realized that this is history. It’s sad history, tragic history, but it’s important history. We need to learn from it to understand how such violence might be prevented in the future. It’s also important to memorialize the 2 million or more lives lost within a space of two and a half years.”

Writing with Memory and Responsibility

Rather than analyzing political causes or assigning blame, Effiong’s first memoir documents what the war felt like to live through — the fear, confusion, and struggle to maintain a sense of normalcy — allowing the brutality of war to speak for itself.

“I didn’t want to take sides,” he said. “I just wanted to present the war the way a child experienced it — what the child saw, what the child felt.”

His second memoir turns to a period Effiong believes is often missing from war narratives: the aftermath, a time when families who had lost everything return to postwar reality and in which properties are gone, businesses collapsed, and bank accounts inaccessible. As part of a national reconciliation effort, the Nigerian government gave families 20 pounds to rebuild their lives, a sum Effiong says is roughly equivalent to $100 today.

“What could that do?” he said. “I saw the impact on my parents, who had to raise eight children after losing their entire means of livelihood. I watched others go through similar struggles with no rehabilitation.”

“I saw the impact on my parents, who had to raise eight children after losing their entire means of livelihood. I watched others go through similar struggles with no rehabilitation.”

For Effiong’s family, and countless others, rebuilding meant starting over with virtually no support. The consequences of the war were economic, social, and psychological, and, Effiong argues, they remain visible in Nigeria today.

“The culture of violence in Nigeria is more widespread than it’s ever been as a result of this war because efforts were never made to condemn violence as a means of getting what we want,” he said. “It’s been there in the military dictatorships. It’s been there in religious conflicts. It’s been there in conflicts over land. My view is that violence wouldn’t be embraced and normalized the way it is if we had not had that war, or if postwar efforts had been made to sincerely address the war crimes and the damages — psychological, mental, and social — to people’s lives. Because that was never done, the culture of violence continues to thrive in Nigeria.”

From Nigeria to MSU

This academic year, Effiong was promoted to Professor in the Department of Theatre. His commitment to history and storytelling is inseparable from his path as an educator. That path began in Nigeria, where he first taught after earning a bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Calabar. Through the National Youth Service Corps, he was assigned to teach in rural communities, an experience that sparked a lifelong commitment to education.

He returned to the University of Calabar for his master’s degree in Literature of the African Diaspora, where his academic interests expanded to include African, Caribbean, and Black American literature. Over time, he recognized that literature cannot be fully understood without a grasp of the historical context, a realization that shaped his interdisciplinary approach to teaching and research.

A Fulbright scholarship later brought him to the United States, where he shifted his focus to theatre. He earned a Ph.D. in Drama from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“I enjoyed all the stories I was dealing with from different parts of the world,” he said, “but I wanted to see them come alive.”

In 2017, he joined the Department of Theatre faculty at MSU, where he teaches theatre, literature, and integrative humanities courses, encouraging students to think beyond familiar frameworks.

“One of my goals is to help students develop a global perspective. Students yearn to be more globally connected, and whatever class I teach, I try to introduce a global perspective to give them more than what they’re already familiar with.”

“One of my goals is to help students develop a global perspective,” he said. “Students yearn to be more globally connected, and whatever class I teach, I try to introduce a global perspective to give them more than what they’re already familiar with.”

Some of his most meaningful moments come when former students reach out to share how his teaching has influenced their lives, including a recent call from a former student who is now a senator in Nigeria.

“That’s my satisfaction,” Effiong said. “Here at MSU, my greatest motivation comes from the students. I really enjoy the mindset of the students, how I engage with them, and what I learn from them.”

Healing Through the Written Word

Writing the memoirs was not only an act of documentation but also a path to healing. As Effiong wrote and spoke with others about the war, he was surprised by the intensity of his memories and the clarity with which they returned. He recognized how much he had internalized and found the writing to be beneficial in his path to healing.

“I didn’t realize how much I was carrying inside,” he said. “As I wrote about my personal experience and what I remember, it’s been very therapeutic. And the more I wrote, the more I realized this needed to come out.”

At times, Effiong sought counseling to better understand how trauma had shaped his confidence, fears, and emotional responses.

“When you bring things into the open and address them in a sincere way,” he said, “it creates a space for healing.”

Effiong points to models such as South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as examples of how societies can confront painful histories. Nigeria, he said, chose a different path by suppressing the narrative and hoping it would fade away.

“People say, ‘don’t reopen old wounds,’” he said, “but how can you reopen something that was never covered to begin with?”

“For too long, this story was suppressed and didn’t receive the attention it deserves. We can’t allow that to happen again.”

Through his books, Effiong hopes to keep the history alive, memorialize those who were lost and helping readers, especially those far removed from war, understand its true cost.

He also seeks to broaden the narrative of the Nigeria–Biafra War by highlighting the experiences of non-Igbo ethnic groups, whose suffering is often overlooked.

“The rest of us fought, starved, and lost family members, businesses, and property. We were destitute after the war,” Effiong said. “Part of my goal is to expand the narrative so the focus isn’t only on the Igbo people.”

While he does not plan to write additional memoirs, he continues to research postwar and transgenerational trauma, examining how the legacy of violence persists even among those born after the conflict ended.

He is encouraged by renewed attention to a history he believes deserves far more recognition. This month he did a book talk at Columbia University, and plans are being made for a book launch in Nigeria.

“I’m hoping other writers who write about this subject also get the attention that this book is receiving,” he said. “For too long, this story was suppressed and didn’t receive the attention it deserves. We can’t allow that to happen again.”

By Austin Curtis and Kim Popiolek